Everywhere you look today you can find discussion about skills (more so than competencies, which we will get into later). There is the need to upskill, re-skill, future-skill, and of course, the looming workforce skills gap crisis. Many studies and reports cite these as critical issues that all business leaders would ignore at their peril:

- 74% of CEOs are concerned about the availability of key skills (PwC, 2020)

- Only 28% of leaders are being developed in critical skills for the future (DDI, 2020)

- Only 29% of new hires are highly prepared with the skills needed for their role (Gartner, 2021)

What’s interesting to note is that the term “skill” is not well understood or defined. The term itself was first used around the 13th century (so it’s old, more on that later). The Oxford English Dictionary defines it as the “capability of accomplishing something with precision and certainty; practical knowledge in combination with ability; cleverness, expertness. Also, an ability to perform a function, acquired or learned from practice.”

This definition does a great job of representing the broadest use of the term “skill.” A skill is basically something that you know how to do. That can include anything from coaching to writing c-sharp code. And I believe that the use of the term “skills” in the statistics above intends the same broad definition.

Competency vs. Skill

In the last few years, certain groups have started to draw a hard line between the term “competency” and the term “skill.” From what I can tell, many of the voices driving the discussion have likely never implemented skills or competencies within organizations.

I came to this conclusion after reading loads of different blog posts from analysts and professional writers hired by companies who are trying to differentiate themselves by talking about a skills-based approach as something new. You can tell that they aren’t practitioners, they are researchers. Their research is only as good as their sources. So they come to the table with some definitions that are a bit misaligned and a bit like a copy of a copy of a copy. The edges get blurred and details start to lose focus.

There also seems to be a general misunderstanding of how competencies are meant to work in practice. If we check back in with our friends over at the Oxford English Dictionary, they define competency as “the ability to do something successfully or efficiently,” and they list one of the synonyms as (you guessed it) “skill.”

My sense after reading many of the articles that advocate for skills over competencies is that the misunderstanding comes from one primary thing—there are a lot of competency DIYers out there, and while well-intentioned they might lack some expertise. As a result, they developed their competencies in ways that become problematic down the road.

The Gap Competencies Fill

Created in the 1970s, competencies are a relatively new idea. Recall that the concept of a skill was born in the 13th century, and in fact, skills have long been much easier to understand, define, and measure.

Consider, for example, the idea of trade skills. Can that person wire an electrical outlet in an office or home correctly? Easy, we have relatively well-defined standards used to evaluate whether the person has the skill to complete that task.

Historically, it has been harder to evaluate things that fall into the soft and general categories. For example, things like coaching, influencing, teamwork, and delegating. Because we have not had universally accepted definitions of what high performance looks like in these areas, competencies were created to fill this gap.

Best Practices for Developing Competencies

There are best practices for how to define competencies. However, many of these best practices fly in the face of some of the criticisms that have been levied against competencies of late, such as being too broad, too multi-faceted, too specific to one job, too full of corporate buzz words, too hard to measure reliably, etc.:

- Linked to requirements: It’s necessary for someone to be skilled to perform well in the job.

- Links strategies and culture: There should be consideration for how the company wants people to behave as part of the culture.

- Distinct: There should be minimal or no overlap between competencies.

- Observable: It should be easy to evaluate someone’s ability by demonstrating the competency. (This means it should not be something going on inside of a person’s head.)

- Reliably interpreted: If one person looks at the definition of a competency and comes away with a different understanding of what high performance looks like, then it’s not well defined, and it’s not going to be reliably evaluated.

- Defines levels of mastery: This goes hand in hand with being distinct, but you need to have meaningful distinctions between one competency, e.g., task delegation, and another level of mastery within the same construct, e.g., empowerment delegation.

If done well, competencies ensure alignment between the business outcomes of the organization and workforce capability. They reduce unconscious bias when evaluating people and create a more inclusive workplace. And they can dramatically increase talent mobility, especially when it comes to leaders.

An Example of How Using Competencies Benefits Organizations

When you speak with talent management professionals, many will tell you that their biggest challenge right now is increasing the diversity of their leadership populations. One of the easiest ways to do this is to create greater talent mobility via lateral moves within an organization. This has multiple positive effects:

- Creates a broader range of meaningful opportunities and experiences for talented people to explore.

- Increases retention because people have more meaningful opportunities.

- Creates better, more empathetic leaders because they can experience other functional areas within the company.

- Leads to better decisions because leaders with cross-functional experience will consider a broader range of implications.

Leadership competencies are an effective catalyst for talent mobility because they are more stable and universal than technical skills. For example, if a leader in marketing moves laterally to a role in operations, will they still need their technical marketing automation skills? Probably not. They may actually need to pick up new technical skills for the operations area. Will they still need to be a great coach to their team? Definitely! Will they still need to be good at influencing stakeholders? 100%!

Technical skills will always be important, but they change frequently at an increasingly rapid pace. This is especially true in leadership positions. Enduring general and soft competencies apply across functional areas and provide ways for leaders to more easily move laterally within an organization.

What a Great Competency Looks Like

Now that we have talked about how competencies can benefit organizations, you might be wondering what a great competency looks like.

Let me offer an example that meets the best practice criteria:

Competency:

Coaching

Definition:

Engaging an individual in developing and committing to an action plan that targets specific behaviors, skills, or knowledge needed to be successful.

Key Actions:

- Describe the purpose and importance of the coaching session; check for understanding.

- Explain the need for improvement or preparation for a new opportunity; share specific examples.

- Acknowledge the person’s contributions and progress without minimizing challenges; empathize with concerns.

- Ask questions to further clarify the issues, challenges, and their causes and collaboratively develop a plan.

- Provide assistance by sharing suggestions for improvement, resources, or opportunities for experimentation.

- Confirm the person’s commitment to the plan.

- Agree on timeline, progress measures, and results.

While there are other definitions of coaching, this one does a good job of meeting best practices because it is clear, observable, and reliably interpreted. It is also likely very similar to other definitions of effective coaching because, let’s face it, good coaching is good coaching.

Where organizations get into trouble is when they DIY their competencies. They inject company buzz words or values mantras, or combine competencies to reduce the total number of competencies. This often ends up muddying the definition of the competency, making it confusing and less functional.

You don’t have to reinvent the wheel. Competencies like coaching, delegating, and influence have been researched and defined repeatedly. So don’t spend your time wordsmithing. For example, you can start with DDI’s competency library which is updated bi-annually based on our research with hundreds of companies.

Dos and Don’ts of Implementing and Managing Leadership Competencies

To achieve results, you need to have more than well-defined leadership competencies (although that’s a great start). You need discipline to implement and manage your competencies.

Here are some “Dos and Don’ts” that will help you ensure your leadership competencies have maximum impact.

| Do | Don’t |

| Integrate your competency model with your business strategy | Let your model be an “HR thing” |

| Focus on observable, reliable behaviors | Use broad, unclear language |

| Differentiate by level, but only where significant | Force-fit competencies by level |

| Identify triggers to update competencies | Spend too much time on your competency framework |

| Operationalize your model into everything you do | Let your model sit on the shelf (or SharePoint site) |

How Competencies and Skills Can Work Together

We can use competencies and skills together to understand all of the important facts. First, recall the distinction between competency and skill:

- Competency – An observable set of behaviors that defines effectiveness in a discrete area of non-technical job performance. E.g., coaching.

- Skill – The ability to apply defined technical expertise required to complete a job task or activity. E.g., JavaScript.

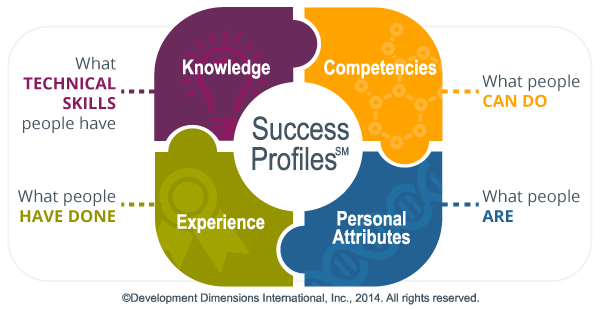

Now let’s look wholistically at how competencies, skills, and other stuff can come together to define a full picture of success in a job, called a Success ProfileSM.

Success Profiles: What Success Looks Like in a Job

The concept of a Success Profile is used by many HR geeks like me to represent the full picture of what it takes for someone to be successful in a job. It typically includes behaviors or competencies, personal attributes, technical skills, and experiences.

As you can see in this diagram, when we consider all of the things needed for success, we can group them into these four areas. This model allows you to get a full picture of what the perfect candidate for a job might look like.

For example, a job may require someone to be great at influencing because they will be working in a matrix organization (influence competency). Or, perhaps they will need to be motivated by ambiguity and have a high degree of resilience because they are working on new innovative solutions (ambiguity tolerance and resilience personal attributes). Or maybe it would be beneficial for them to have knowledge of working with AWS (technical skill) and also experience working in the business-to-consumer technology space (experience).

All of these can together represent the ideal person for a given job. Of these areas, competencies and personal attributes are harder to develop and more transferable across jobs. This is especially true when it comes to leadership roles.

The Value of Competency-Based Leadership Development

According to our most recent leadership forecast survey of thousands of leaders and HR practitioners worldwide, organizations that clearly define leadership competencies and use them to design and deliver leadership development programs have:

- 1.8 times higher leadership quality

- 1.4 times higher leadership success rates

- 1.5 times stronger bench strength

Leadership competencies are almost always at the heart of the programs that drive strong impact. Here are a few of the top value drivers for competency-based leadership programs:

- Determine the potential readiness/risk for leaders to implement a new strategy.

- Align leadership and professional development programs with the competencies that will lead to successful execution of current strategies.

- Hire and promote leaders who have the competencies needed to be successful given the current organizational strategies.

- Increase the objectivity and reduce the bias associated with leadership evaluations and promotion decisions.

Competencies Create Meaningful Work Experiences

Most people, leaders included, want to do meaningful work that has a meaningful impact. To do that, they need to know what great looks like. Well-defined competencies can define success, and programs that help leaders develop in specific competency areas will increase their capability and confidence. Additionally, objective standards of evaluation for development, hiring, and promotion will create more diverse populations of leaders and greater fairness across the board.

In the end, it’s not about whether competencies or skills are better—they are both important. It’s about being clear on our definitions of those two things and knowing when and why we use them to help leaders and organizations be successful. Effectively used competencies and skills lead to better leaders, better business outcomes, better employee experience, and ultimately, a better future.

Learn how DDI does competencies differently.

Ryan Heinl is Director of Product Management and Leader of DDI’s Innovation Lab, where he brings innovative leadership solutions to life. He is an entrepreneur, writer, chef, CrossFitter, mindfulness junkie, and occasional yogi who travels the world in search of the perfect moment (and secretly hopes he won’t find it).

Topics covered in this blog